The seeds of Alzheimer’s disease may have been transmitted along with human growth hormone into eight British patients treated decades ago, according to a study published Thursday in Nature. If supported by further research, the findings imply Alzheimer’s could potentially be transmitted via close contact with the brain tissue of someone who has the disease.

That does not mean Alzheimer’s is contagious, researchers are quick to note. These eight patients all received doses of human growth hormone from the pituitary glands of numerous cadavers—a very unusual transmission route.

If there is any risk of Alzheimer’s transmission—and there have been no proved cases of this—it is likely only from surgical instruments, the new study’s senior author, John Collinge, said Wednesday in a news conference. The University College London neurologist added he hopes future research will investigate whether Alzheimer’s could be seeded by certain medical procedures and whether new techniques are needed to sterilize neurosurgical instruments to ensure that does not happen.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

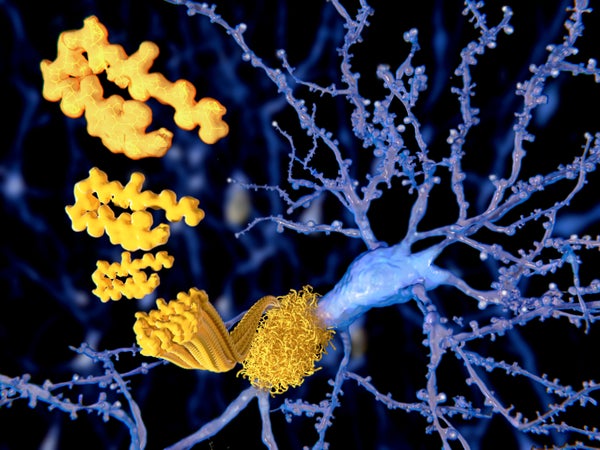

All eight patients in the study had received human growth hormone as children because of various growth-related conditions. Growth hormone from the human pituitary gland was replaced with synthetic hormone in 1985 after scientists realized that using the human version could—in rare instances—transmit Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, the human form of a neurodegenerative disease also known as “mad cow disease.” The same contaminated hormones that carried Creutzfeldt to the eight patients also apparently transmitted a protein called amyloid beta, clumps of which are a defining characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Collinge said he detected the amyloid beta, in the patients’ brains and blood vessels. All eight were in their 30s and 40s—too young, he says, for so much of the protein to be present normally. He also eliminated other possible causes for the amyloid’s presence. It was not caused by the patients’ underlying growth problems, he said, because all eight had different issues and there have been no previous connections between growth issues and amyloid. And it was not caused by the growth hormone itself, he said, because mice injected with synthetic growth hormone showed no unusual amyloid buildup.

Collinge then tested vials of the human growth hormone that the eight patients received, which had been saved for decades in powdered form on a shelf at room temperature. There were several different methods for purifying the growth hormone. The samples in which he detected amyloid were prepared the same way was as those that seem to have transmitted Creutzfeldt, so Collinge thinks this method must have allowed more contaminants to remain.

In addition to Creutzfeldt–Jakob, the patients all developed a condition called cerebral Aβ−amyloid angiopathy, which is present in 90 percent of Alzheimer’s patients. The eight patients did not live long enough for scientists to determine whether they would have developed Alzheimer’s, Collinge said. He is now doing experiments to see whether the patients could have received another protein associated with Alzheimer’s, called tau, from the contaminated growth hormone samples. If they did, that would add to the evidence Alzheimer’s is potentially transmissible, he said.

Stephen Salloway, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Brown University who was not part of the work, says the new study and the idea of transmissibility is supported by growing evidence from animal models that the disease process can be triggered by injecting brain tissue from Alzheimer’s patients into animal brains. “These important findings provide additional clues and new models for testing,” he wrote via e-mail. “Increased understanding of the mechanisms underlying Alzheimer’s disease will lead to early interventions with effective treatments that modify the course of the disease.”

Other researchers have proposed viruses might be the initial trigger for Alzheimer’s or that misfolded proteins called prions, as seen in Creutzfeldt, could be the culprit.

Paul Aisen, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of Southern California’s Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, says he does not think people should worry about Alzheimer’s being transmissible. “I am not convinced it should be a concern,” he says. “I don’t think the evidence points to transmissibility of Alzheimer’s.”

But Aisen notes we still know so little about the disease that all types of research remain important. “I fully support investigating all these lines of study—viruses, prions, transmissibility—all these things are worthy areas of investigation until we understand the disease well enough to develop proven therapies.”